Hello, World! without BIOS

16 Nov 2018You probably studied (or pursued) Computer Organization at some point, you know how hardware works basically, maybe you even tried playing with Arduino or AVR (or even better, ARM). But how does your computer work? what happens when you push that power button?

You probably also heard of BIOS and the magic stuff it does to boot your computer.. but how does it work under the hood? could you write your own BIOS?

That’s exactly what we will do, make our computer do something without the BIOS (i.e. write our BIOS-like thingy).

Prerequisites

- Basics of Computer Organization

- Basics of Assembly

- Using a Linux based distro (if not, you know what you are doing)

nasmandqemuare installed

Power on sequence

When you push the power button, the motherboard powers on the CPU (there is no definitive way of how this occurs, we only concern ourselves with how the CPU sees it). The processor starts by doing some initialization steps (like choosing the bootstrap processor in a multi-processor setup) and then goes into a known defined state (it wouldn’t make sense otherwise, imagine the processor goes executing code from mars on power up). To know that state, we should consult the manual of the processor.

For our experiment, the most concerning values are

EIP = 0000FFF0H

CS:

Selector = F000H

Base = FFFF0000H

Limit = FFFFH

This means that the processor starts execution in real-address mode from EIP = 0xFFFFFFF0 (the last 16 bytes of 4GB memory).

Q: But how is that possible when the processor can access only 1MB of memory in real-address mode?

A: The processor uses a trick, since in real-address mode segment bases were not yet introduced, the processor always uses the base address of the segment regardless of the addressing mode. But in real-address mode when you flush any segment selector it sets both the segment selector and the base simultaneously so it would be compliant with real-address mode specifications.

At start up, the code segment selector is 0xF000 just as in older versions of the processor, however, the base is 0xFFFF0000, internally the Bus Interface Unit (BIU) uses the base address of the segment regardless of the currently active mode. This has the irritating effect that if you do a far jump inside the firmware code block, the segment will get flushed and the base address would be lost and you can no longer access the code (unless you jump to protected mode).

For further details on how this works, check out section Processor State After Reset in

How Qemu loads BIOS file

Since x86 starts execution from the very last 16 bytes of the very last segment in memory, Qemu requires the BIOS file to be an exact multiple of segment size (64k) and will be loaded in location 0x100000000 - s, where s is the file size in bytes (currently the maximum limit of s in qemu is 8MB, you can check the current value by locating FLASH_MAP_BASE_MIN inside /hw/i386/pc_sysfw.c in qemu source tree).

For example, our nobios BIOS will be exactly one segment, so s = 64k = 0x10000 and hereby will be loaded in memory location 0xFFFF0000

Qemu also aliases the last 128k of memory to 128k below 1MB, so everything between 0xFFFE0000-0xFFFFFFFF will be also accessible through 0xE0000-0xFFFFF.

Qemu has a list of pre-compiled BIOS files listed in some particular directories, to know these directories use the command:

$ qemu-system-i386 -L help

then you can ls these directories and check the files in them.

Simple BIOS

Let’s write the simplest code ever, one that does absolutely nothing. In theory, the following assembly code would be sufficient

jmp $However, it still relies on us to get that jmp instruction to be located exactly at 0xFFFFFFF0, and that our flat binary image would be 64kB in size.

Since our file is loaded at 0xFFFF0000, we can fill everything up to 0xFFFFFFF0 with zeros, to do that we use NASM times

; Our file is loaded at 0xFFFF0000, we offset that by 0xFFF0 to get 0xFFFFFFF0

times 0xFFF0 - ($ - $$) db 0

; Execution starts here

jmp $We can use the same trick to get the file to 64k in size, by filling it with zeros until it reaches 0x10000

; Our file is loaded at 0xFFFF0000, we offset that by 0xFFF0 to get 0xFFFFFFF0

times 0xFFF0 - ($ - $$) db 0

; Execution starts here

jmp $

; Our file must be exactly 64k in size

times 0x10000 - ($ - $$) db 0to assemble this file into a (flat) binary image, use the following command

$ nasm -f bin -o bios.bin bios.asm

and to run it, use

$ qemu-system-i386 -bios bios.bin

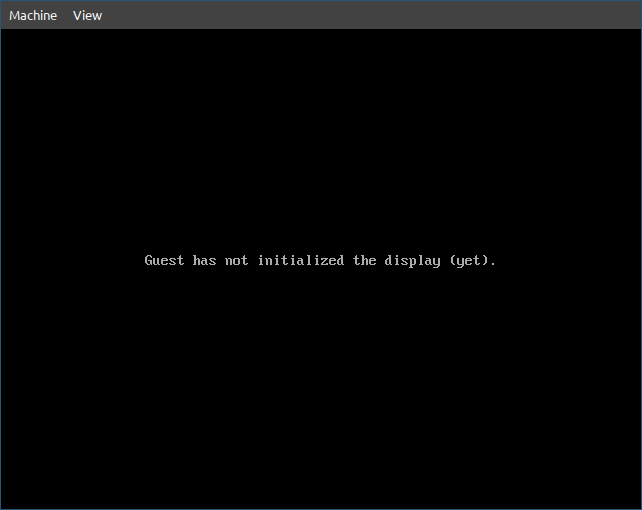

If everything goes well, you should be presented with this

which is great, it didn’t crash, so it must be working. You can try commenting that jmp instruction and loading the file again, qemu will crash with a lovely message (I leave that to your adventurous soul).

Since we will work on this file for a while, let’s be lazy about things.

Let’s create a Makefile so it would be easier for us to assemble and run the file anytime.

NASM := nasm

QEMU := qemu-system-i386

OBJ := nobios.bin

.PHONY: all

all: $(OBJ)

nobios.bin: nobios.asm

$(NASM) -f bin -o $@ $<

.PHONY: run clean

run: nobios.bin

$(QEMU) -bios $<

clean:

$(RM) -f $(OBJ)Then we can assemble and run the file with one command

$ make run

Using UART for output

Our nobios BIOS works, it sends the machine into a blackhole of nothingness, but it would be anti-climax if we don’t make it do something. So let’s show something up, unfortunately, VGA is too hard to initialize for our simple demo, so let’s use something simpler (and a bit more interesting). The original PC was equipped with a UART controller (Intel 8250), which Qemu emulates pretty nicely.

Initializing the UART driver is quite simple, we just identify its port numbers, set some configuration registers and start sending stuff.

Putting it all together

%define fill(x) times x - ($ - $$) db 0

%macro inb 1 ; (port) => returns al

mov dx, %1 ; port

in al, dx

%endmacro

%macro outb 2 ; (port, value)

mov dx, %1 ; port

mov al, %2 ; value

out dx, al

%endmacro

%define PORT 0x3F8

uart_init:

; Disable all interrupts

outb (PORT + 1), 0x00

; Enable DLAB to set baudrate divisor (base=115200)

outb (PORT + 3), 0x80

; Set divisor low byte to 1

outb (PORT + 0), 0x01

; Set divisor high byte to 0

outb (PORT + 1), 0x00

; 8 bits, no parity, one stop bit

outb (PORT + 3), 0x03

ret

uart_putc:

inb (PORT + 5)

and al, 0x20

jz uart_putc

outb PORT, bl

ret

uart_puts:

mov bl, byte [ds:si]

or bl, bl

jz .done

call uart_putc

inc si

jmp uart_puts

.done:

ret

_start:

call uart_init

mov ax, 0xF000

mov ds, ax

mov si, msg

call uart_puts

jmp $

msg: db "Hello, World!", 0

; Our file is loaded at 0xFFFF0000, we offset that by 0xFFF0 to get 0xFFFFFFF0

fill(0xFFF0)

; Execution starts here

jmp 0xF000:_start

; Our file must be exactly 64k in size

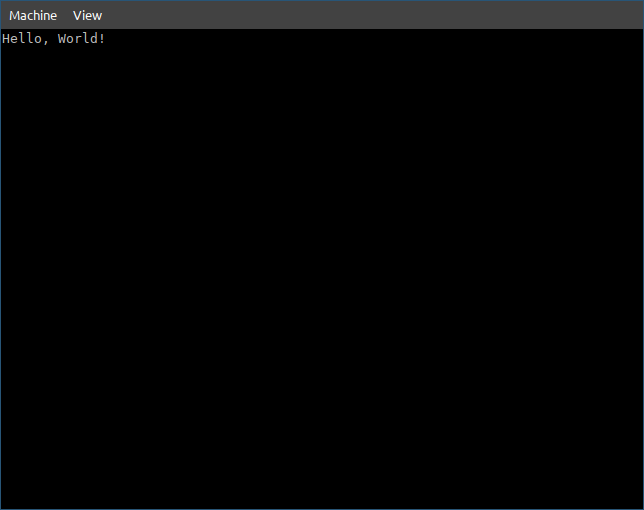

fill(0x10000)If we run the command

$ make run

It still shows the same thing, which is OK, we didn’t initialize VGA, to see the serial port output

View > serial0 (or press Ctrl+Alt+3).

Voilà! Welcome to the 80s!